In September 2022, 22-year-old Mahsa Amini was walking along the streets of Tehran when she was arrested by Iran’s morality police for a hijab-related “dress code violation.” She was taken to a nearby police station and beaten into a coma. Three days later, she succumbed to her wounds.

Her death sparked outrage among Iran’s youth and inspired the largest protests in the regime since 2009. Hundreds of protesters were killed by Iranian forces in the days that followed.

In the wake of Mahsa Amini’s murder, Iranian dissident Golbon Marandiz penned a poem of defiance called “40 days and counting.”

The poem reads in part:

Acid rain from the eyes of her people

Anger and grief and guilt,

Burning the crumbling foundations of the regime.

Hear her roar,

Amplify her voice.

See her rise,

Use your voice

Let her songs of women, life, freedom

Echo vastly beyond your ears,

Carry on the chorus!

Save your tears.

Instead, chant the anthem of

The lionhearted empire:

Heart songs, the children of Cyrus,

When her voice gets coarse,

Lend her yours.

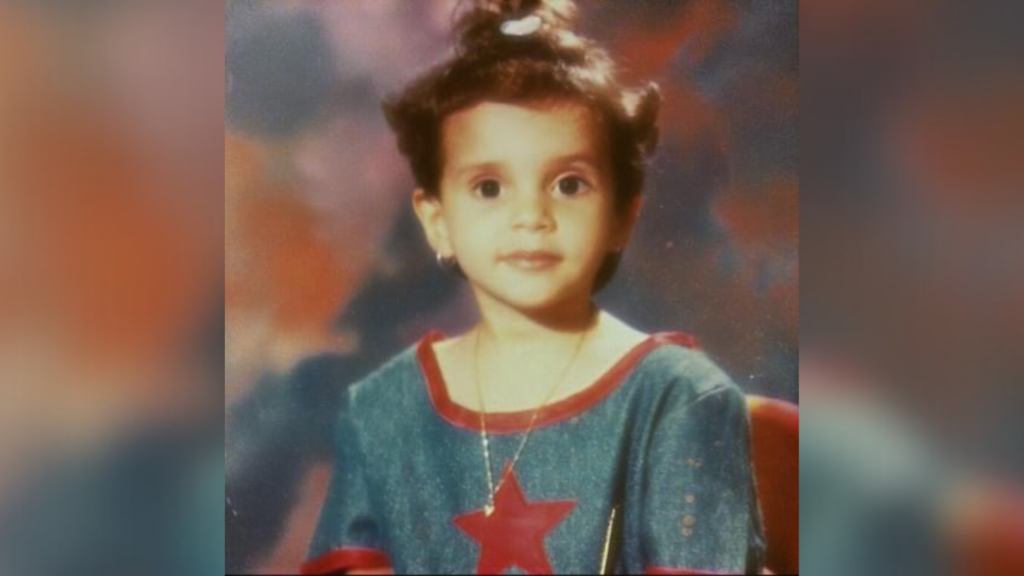

Speaking to IW Features, Marandiz recalled how Amini’s death in police custody resurrected memories of her own childhood in Iran.

“I remember the weight of being a girl in society,” she said. “I felt the fear when my mother’s hijab would fall off in the wind, and I watched her frantically put it back on. I felt it when a grown man tried to kiss your lips, knowing that my body was a thing of shame that I was taught to cover.”

Marandiz recalls her hijab — the head covering that women and girls older than 9 years old have been required to wear in Iran since 1981 — feeling like a “dark cloud” above her head. “That finally went away when we stepped off the plane in Turkey,” she said, “and my mother took her hijab off at the gate.”

***

Marandiz was born in Tehran, Iran, in 1995, 16 years after the Iranian Revolution, when the fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty and the rise of the Islamic Republic restructured Middle Eastern society.

On the eve of the revolution, one-third of university students in Iran were women. Two million women were in the workforce, 146,000 of whom were in civil service. More than 300 women served on elected local government councils, and 22 women sat in parliament.

After the revolution and under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, however, women quickly disappeared from public life.

Pictures of this era serve as a grim reminder of the fragility of freedom — miniskirted women dressed in quintessential western 70’s garb one day and in black hijabs the next. Photos of 100,000 women, many of whom would be attacked or stabbed, flooding the streets on March 8th, 1979, to protest mandatory veiling draw an eerie parallel to the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests that followed Amini’s death in 2022.

Marandiz’s family, who practiced the Baha’i faith, faced unique persecution. In the decade following the revolution, more than 200 Baha’is were executed by Iran’s new leadership. Hundreds more were imprisoned and tortured. Thousands lost educational opportunities and jobs and were stripped of basic human rights. A relentless propaganda campaign was launched against the Baha’i people through the press, online media, and educational institutions. The problem persists — since 2017, more than 33,000 pieces of anti-Baha’i content have been published in Iran.

“They say we’re dirty, we’re foreign, we’re heretics. We were really a very peaceful community,” Marandiz said.

The nineteenth-century faith, established by Baha’u’llah in Iran, teaches a pluralistic three-pillared doctrine, including the unity of God, unity of religion, and unity of humanity. It also emphasizes the equality of the sexes. “Baha’u’llah preached equality between men and women, saying that we are wings of one bird. Without the other, we cannot fly,” Marandiz said.

“My mother would take us to Sunday school gatherings in secret. People would gather together and pray and share food and stories. I was so confused as to why the world hated us, why I couldn’t tell people I was Baha’i,” she added.

The persecution reached a fever pitch at school. Marandiz remembers being segregated from her class, humiliated by teachers, and treated as a second class citizen. “Educators would make students chant “death to America, death to Israel” and make children “walk over American flags and burn Israeli flags.” She was ridiculed for refusing to participate.

“I felt this shame, this dirtiness, this sense of having to safeguard my heart. I had to hide who I was as a child,” Marandiz said.

As Marandiz reached high school, her parents became increasingly worried. “They became reluctant to send me, because of what happens to Baha’i women at school,” she said.

This increasingly hostile environment, coupled with the discrimination and belligerent state harassment towards her father’s business, catalyzed the decision to immigrate. “My parents knew we had to leave if we wanted to have a chance at a life. They knew it was time to make our escape for safety, for prosperity, for America,” Marandiz said.

***

In 2000, when Marandiz was 16 years old, her family surrendered their belongings and sought asylum in Turkey. There, they settled in a small flat with another family overlooking a dump.

After nine months of waiting, the family received approval to migrate to the United States.

When they landed in Redmond, Washington, they had $4 left to their name. Her father worked in construction and plumbing, and her mother became pregnant with her sister.

Marandiz immediately recognized a shift in her mother as she tasted newfound freedom.

“After giving birth to my sister, she went out and got a job as a preschool teacher while still learning English,” Marandiz said. “I’d never seen her work before. She could go out without having to ask permission from my father or cover[ing] her face with a hijab. I saw her gain her confidence back.”

After divorcing her father in 2010, Marandiz’s mother bought a house in Texas in 2014. “She worked two jobs until she was awarded a higher position at Sam’s Club. She was the sole provider for my sister and I,” Marandiz said.

“She taught me just how much freedom can change your life.”

The young Marandiz was indecisive about her own career path until the murder of Mahsa Amini. “When the revolution started in 2022, protestors were dying in the streets — over 300 political prisoners have been executed this year alone. Poets and artists were being arrested and disappeared. As a poet myself, seeing that was especially hard.”

In particular, Marandiz was alarmed at how “internet capability was limited to silence dissidents and discourage assembly.”

This year, Marandiz enrolled at the University of Washington in Seattle, studying informatics with a focus in cybersecurity to help Iranians evade government censorship. Soon after, she began an internship in data analysis with the Ayaan Hirsi Ali Foundation, an organization dedicated to advancing women’s rights and pushing back against Islamic extremism. In the summer of 2024, she joined the Dissident Project to share her story with high schoolers across the country.

“It’s scary to speak up, but it’s scarier to live under censorship and extremism,” Marandiz said, imploring young people to raise their voices. “The people that are loudest are the most extreme — pragmatic youth have been afraid to speak up. Think past the fear, for the sake of your freedoms.”

Her admonitions echo the rallying cry in her poem, “40 days and counting”:

Remember her name

Remember her fight

Because freedom is never free

Yet, it’s our God-given right.